Norwegians go to the polls on Sunday and Monday in a tight race to decide whether to continue with a Labour-led government or turn to the centre right.

There are only four million voters in this founding member of Nato, which shares an Artic border with Russia and is part of the EU’s single market but not a member state.

Despite its small population, Norway has long punched above its weight on the international stage, and the wars in Gaza and Ukraine – as well as US trade tariffs – have played a significant part in the election campaign.

Nevertheless, in the final stretch of the race, the focus has switched to the increasing cost of living and inequality.

“Public spending, school and infrastructure, railway infrastructure and road construction, those kinds of things,” says Andreas, who is father to a small child, about what he considers the key issues.

This domestic focus became clear during Norway’s summer politics fest in the small town of Arendal, last month.

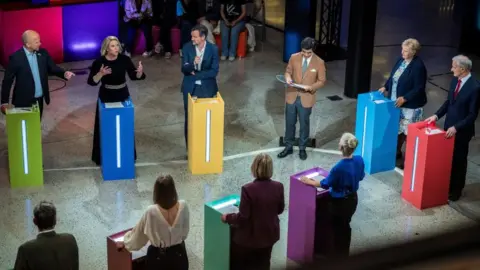

Every year, Norway’s political class joins company bosses, unions and the public on the south-east coast for an array of panel talks and meetings. This time, it opened with a nationally televised election debate in which all the main political leaders took part.

Among them was Labour Prime Minister Jonas Gahr Støre, 65, who is aiming for a second term in office after eight years of conservative rule ended in 2021.

He is fighting off a challenge from a bloc made up of two conservative parties: the right-wing populist Progress Party under Sylvi Listhaug, 47, which has risen in popularity, and the Høyre party of ex-Prime Minister Erna Solberg, which is looking to return to power.

One of the hot-button issues of the campaign has been the future of a 1% wealth tax, which Norwegians pay if their assets add up to more than 1.76m Norwegian kroner (£130,000; $175,000).

Hundreds of wealthy Norwegians have already left the country for Switzerland in recent years, anecdotally because of their native country’s high taxes.

Can that exodus be reversed?

Sylvi Listhaug has called for the abolition of the wealth tax and cutting other taxes too, while Solberg’s conservatives want to remove the wealth tax on what they call “working capital”, such as shares.

Labour refuses to go that far but has promised a wide-ranging review of taxation. It has heavyweight former Nato chief Jens Stoltenberg in charge of finance and he warns against creating a tax system that means the wealthiest in Norway end up paying little or no tax.

Opinion polls ahead of the vote have put Labour in the lead, ahead of Listhaug’s Progress party and the conservatives, and buoyed partly by the “Stoltenberg effect”.

But if the combined forces of the centre right win, one of the big questions of this election is which of the two party leaders would be prime minister.

Solberg, 67, who was prime minister for eight years, has so far refused to accept the idea that her populist rival could take office ahead of her, suggesting that voters see her as too polarising as a politician.

Foreign policy has rarely been far away from the election campaign, and recent weeks have been dominated by a move by Norway’s sovereign wealth fund – the world’s largest – to scrap investments in almost half the Israeli companies it held because of alleged rights violations.

The $1.9tn (£1.4tn) fund, built up over decades from Norway’s enormous oil and gas resources, is managed by the central bank but it has to follow ethical guidelines.

Buffeted by political headwinds surrounding the Gaza war, the fund’s chief executive Nicolai Tangen, has described its recent decisions as “my worst-ever crisis”.

Although Norway is part of Nato, it has never been part of the European Union.

It does have access to the EU’s single market through its membership of the European Economic Area, so it has to respect its rules. And it is part of the EU’s border-free Schengen zone.

Russia’s war in Ukraine may have brought Norway closer to its European neighbours on a range of levels, but the question of joining the EU has been barely touched on during the election campaign as parties are wary of losing voters on such a polarising issue.

“There’s still a massive ‘no vote’ in Norway. And so the voters are not there,” said journalist Fredrik Solvang, who was one of the moderators of the TV debate in Arendal.

For Solberg’s conservatives, working actively towards EU membership is a core policy, but it would have to be based on a referendum.

“So it’s not about this election campaign,” she told the BBC. “And of course, as long as we don’t see a clearer move towards a majority for EU membership, none of us will start a new debate about the referendum.”

“The Labour Party has always been pro-EU, but it’s not a topic on the agenda today,” said foreign minister Espen Barth Eide.

“I’m not precluding that it could happen in the future if major things happen, but right now, my mandate as foreign minister is to try to maintain as best as possible the relationship as we have it.”

Part of the TV debate in Arendal featured a duel between party leaders from the same side in politics.

When two parties on the centre right – the Liberals who want to join the EU and the Christian Democrats who don’t – were offered a choice between the EU or Pride flags in schools, they preferred to discuss flags.

“I guess with the geopolitical status, it’s an unsure future and I think that we maybe have to take the discussion seriously,” said Iver Hoen, a nurse.

Christina Stuyck, who has both Norwegian and Spanish nationality, agrees.

“I think Norwegian politics kind of acts as if it’s on a separate island to the rest of the world and isn’t affected, but clearly it is.”

Norway’s political system requires parties to attract 4% of the vote to get into parliament, and because it has proportional representation no party can govern on its own.

To form a majority in the 169-seat Storting, a coalition needs 85 seats, and minority governments have long been common in Norway.

Støre’s Labour Party formed a minority government with the Centre party after the last election, but that two-party coalition collapsed in January in a row over EU energy policies.

The centre-right bloc has its own disagreements, so this election may end up with no clear majority when votes are counted on Monday evening.

[BBC]